Leading is establishing direction and influencing others to follow that direction. But this definition isn't as simple as it sounds because leadership has many variations and different areas of emphasis.

Common to all definitions of leadership is the notion that leaders are individuals who, by their actions, facilitate the movement of a group of people toward a common or shared goal. This definition implies that leadership is an influence process.

The distinction between leader and leadership is important, but potentially confusing. The leader is an individual; leadership is the function or activity this individual performs. The word leader is often used interchangeably with the word manager to describe those individuals in an organization who have positions of formal authority, regardless of how they actually act in those jobs. But just because a manager is supposed to be a formal leader in an organization doesn't mean that he or she exercises leadership.

An issue often debated among business professionals is whether leadership is a different function and activity from management. Harvard's John Kotter says that management is about coping with complexity, and leadership, in contrast, is about coping with change. He also states that leadership is an important part of management, but only a part; management also requires planning, organizing, staffing, and controlling. Management produces a degree of predictability and order. Leadership produces change. Kotter believes that most organizations are underled and overmanaged. He sees both strong leadership and strong management as necessary for optimal organizational effectiveness.

Theories abound to explain what makes an effective leader. The oldest theories attempt to identify the common traits or skills that make an effective leader. Contemporary theorists and theories concentrate on actions of leaders rather than characteristics.

A number of traits that appear regularly in leaders include ambition, energy, the desire to lead, self‐confidence, and intelligence. Although certain traits are helpful, these attributes provide no guarantees that a person possessing them is an effective leader. Underlying the trait approach is the assumption that some people are natural leaders and are endowed with certain traits not possessed by other individuals. This research compared successful and unsuccessful leaders to see how they differed in physical characteristics, personality, and ability.

A recent published analysis of leadership traits (S.A. Kirkpatrick and E.A. Locke, “Leadership: Do Traits Really Matter?” Academy of Management Executive 5 [1991]) identified six core characteristics that the majority of effective leaders possess:

- Drive. Leaders are ambitious and take initiative.

- Motivation. Leaders want to lead and are willing to take charge.

- Honesty and integrity. Leaders are truthful and do what they say they will do.

- Self‐confidence. Leaders are assertive and decisive and enjoy taking risks. They admit mistakes and foster trust and commitment to a vision. Leaders are emotionally stable rather than recklessly adventurous.

- Cognitive ability. Leaders are intelligent, perceptive, and conceptually skilled, but are not necessarily geniuses. They show analytical ability, good judgment, and the capacity to think strategically.

- Business knowledge. Leaders tend to have technical expertise in their businesses.

Traits do a better job at predicting that a manger may be an effective leader rather than actually distinguishing between an effective or ineffective leader. Because workplace situations vary, leadership requirements vary. As a result, researchers began to examine what effective leaders do rather than what effective leaders are.

Whereas traits are the characteristics of leaders, skills are the knowledge and abilities, or competencies, of leaders. The competencies a leader needs depends upon the situation.

- These competencies depend on a variety of factors:

- The number of people following the leader

- The extent of the leader's leadership skills

- The leader's basic nature and values

- The group or organization's background, such as whether it's for profit or not‐for‐profit, new or long established, large or small

- The particular culture (or values and associated behaviors) of whomever is being led

To help managers refine these skills, leadership‐training programs typically propose guidelines for making decisions, solving problems, exercising power and influence, and building trust.

Peter Drucker, one of the best‐known contemporary management theorists, offers a pragmatic approach to leadership in the workplace. He believes that consistency is the key to good leadership, and that successful leaders share the following three abilities which are based on what he refers to as good old‐fashioned hard work:

- To define and establish a sense of mission. Good leaders set goals, priorities, and standards, making sure that these objectives not only are communicated but maintained.

- To accept leadership as a responsibility rather than a rank. Good leaders aren't afraid to surround themselves with talented, capable people; they do not blame others when things go wrong.

- To earn and keep the trust of others. Good leaders have personal integrity and inspire trust among their followers; their actions are consistent with what they say.

In Drucker's words, “Effective leadership is not based on being clever, it is based primarily on being consistent.”

Very simply put, leading is establishing direction and influencing others to follow that direction. Keep in mind that no list of leadership traits and skills is definitive because no two successful leaders are alike. What is important is that leaders exhibit some positive characteristics that make them effective managers at any level in an organization.

No matter what their traits or skills, leaders carry out their roles in a wide variety of styles. Some leaders are autocratic. Others are democratic. Some are participatory, and others are hands off. Often, the leadership style depends on the situation, including where the organization is in its life cycle.

The following are common leadership styles:

- Autocratic. The manager makes all the decisions and dominates team members. This approach generally results in passive resistance from team members and requires continual pressure and direction from the leader in order to get things done. Generally, this approach is not a good way to get the best performance from a team. However, this style may be appropriate when urgent action is necessary or when subordinates actually prefer this style.

- Participative. The manager involves the subordinates in decision making by consulting team members (while still maintaining control), which encourages employee ownership for the decisions.

A good participative leader encourages participation and delegates wisely, but never loses sight of the fact that he or she bears the crucial responsibility of leadership. The leader values group discussions and input from team members; he or she maximizes the members' strong points in order to obtain the best performance from the entire team. The participative leader motivates team members by empowering them to direct themselves; he or she guides them with a loose rein. The downside, however, is that a participative leader may be seen as unsure, and team members may feel that everything is a matter for group discussion and decision.

- Laissez‐faire (also called free‐rein). In this hands‐off approach, the leader encourages team members to function independently and work out their problems by themselves, although he or she is available for advice and assistance. The leader usually has little control over team members, leaving them to sort out their roles and tackle their work assignments without personally participating in these processes. In general, this approach leaves the team floundering with little direction or motivation. Laissez‐faire is usually only appropriate when the team is highly motivated and skilled, and has a history of producing excellent work.

Many experts believe that overall leadership style depends largely on a manager's beliefs, values, and assumptions. How managers approach the following three elements—motivation, decision making, and task orientation—affect their leadership styles:

- Motivation. Leaders influence others to reach goals through their approaches to motivation. They can use either positive or negative motivation. A positive style uses praise, recognition, and rewards, and increases employee security and responsibility. A negative style uses punishment, penalties, potential job loss, suspension, threats, and reprimands.

- Decision making. The second element of a manager's leadership style is the degree of decision authority the manager grants employees—ranging from no involvement to group decision making.

- Task and employee orientation. The final element of leadership style is the manager's perspective on the most effective way to get the work done. Managers who favor task orientation emphasize getting work done by using better methods or equipment, controlling the work environment, assigning and organizing work, and monitoring performance. Managers who favor employee orientation emphasize getting work done through meeting the human needs of subordinates. Teamwork, positive relationships, trust, and problem solving are the major focuses of the employee‐oriented manager.

Keep in mind that managers may exhibit both task and employee orientations to some degree.

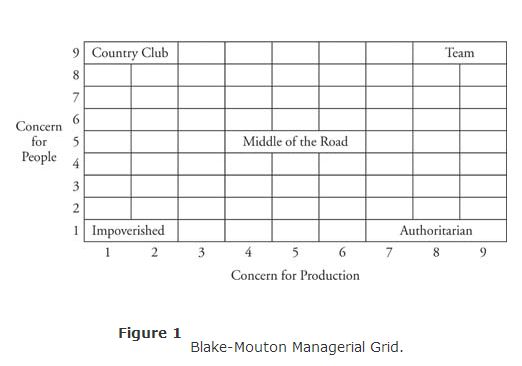

The managerial grid model, shown in Figure and developed by Robert Blake and Jane Mouton, identifies five leadership styles with varying concerns for people and production:

- The impoverished style, located at the lower left‐hand corner of the grid, point (1, 1), is characterized by low concern for both people and production; its primary objective is for managers to stay out of trouble.

- The country club style, located at the upper left‐hand corner of the grid, point (1, 9), is distinguished by high concern for people and a low concern for production; its primary objective is to create a secure and comfortable atmosphere where managers trust that subordinates will respond positively.

- The authoritarian style, located at the lower right‐hand corner of the grid, point (9,1), is identified by high concern for production and low concern for people; its primary objective is to achieve the organization's goals, and employee needs are not relevant in this process.

- The middle‐of‐the‐road style, located at the middle of the grid, point (5, 5), maintains a balance between workers' needs and the organization's productivity goals; its primary objective is to maintain employee morale at a level sufficient to get the organization's work done.

- The team style, located at the upper right‐hand of the grid, point (9, 9), is characterized by high concern for people and production; its primary objective is to establish cohesion and foster a feeling of commitment among workers.

The Managerial Grid model suggests that competent leaders should use a style that reflects the highest concern for both people and production—point (9, 9), team‐oriented style.

Effective leaders develop and use power, or the ability to influence others. The traditional manager's power comes from his or her position within the organization. Legitimate, reward, and coercive are all forms of power used by managers to change employee behavior and are defined as follows:

- Legitimate power stems from a formal management position in an organization and the authority granted to it. Subordinates accept this as a legitimate source of power and comply with it.

- Reward power stems from the authority to reward others. Managers can give formal rewards, such as pay increases or promotions, and may also use praise, attention, and recognition to influence behavior.

- Coercive power is the opposite of reward power and stems from the authority to punish or to recommend punishment. Managers have coercive power when they have the right to fire or demote employees, criticize them, withhold pay increases, give reprimands, make negative entries in employee files, and so on.

Keep in mind that different types of position power receive different responses in followers. Legitimate power and reward power are most likely to generate compliance, where workers obey orders even though they may personally disagree with them. Coercive power most often generates resistance, which may lead workers to deliberately avoid carrying out instructions or to disobey orders.

Unlike external sources of position power, personal power most often comes from internal sources, such as a person's special knowledge or personality characteristics. Personal power is the tool of a leader. Subordinates follow a leader because of respect, admiration, or caring they feel for this individual and his or her ideas. The following two types of personal power exist:

- Expert power results from a leader's special knowledge or skills regarding the tasks performed by followers. When a leader is a true expert, subordinates tend to go along quickly with his or her recommendations.

- Referent power results from leadership characteristics that command identification, respect, and admiration from subordinates who then desire to emulate the leader. When workers admire a supervisor because of the way he or she deals with them, the influence is based on referent power. Referent power depends on a leader's personal characteristics rather than on his or her formal title or position, and is most visible in the area of charismatic leadership.

The most common follower response to expert power and referent power is commitment. Commitment means that workers share the leader's point of view and enthusiastically carry out instructions. Needless to say, commitment is preferred to compliance or resistance. Commitment helps followers overcome fear of change, and it is especially important in those instances.

Keep in mind that the different types of power described in this section are interrelated. Most leaders use a combination of these types of power, depending on the leadership style used. Authoritarian leaders, for example, use a mixture of legitimate, coercive, and reward powers to dictate the policies, plans, and activities of a group. In comparison, a participative leader uses mainly referent power, involving all members of the group in the decision‐making process.