The Decision‐Making Process

Quite literally, organizations operate by people making decisions. A manager plans, organizes, staffs, leads, and controls her team by executing decisions. The effectiveness and quality of those decisions determine how successful a manager will be.

Managers are constantly called upon to make decisions in order to solve problems. Decision making and problem solving are ongoing processes of evaluating situations or problems, considering alternatives, making choices, and following them up with the necessary actions. Sometimes the decision‐making process is extremely short, and mental reflection is essentially instantaneous. In other situations, the process can drag on for weeks or even months. The entire decision‐making process is dependent upon the right information being available to the right people at the right times.

The decision‐making process involves the following steps:

1.Define the problem.

2.Identify limiting factors.

3.Develop potential alternatives.

4.Analyze the alternatives.

5.Select the best alternative.

6.Implement the decision.

7.Establish a control and evaluation system.

Define the problem

The decision‐making process begins when a manager identifies the real problem. The accurate definition of the problem affects all the steps that follow; if the problem is inaccurately defined, every step in the decision‐making process will be based on an incorrect starting point. One way that a manager can help determine the true problem in a situation is by identifying the problem separately from its symptoms.

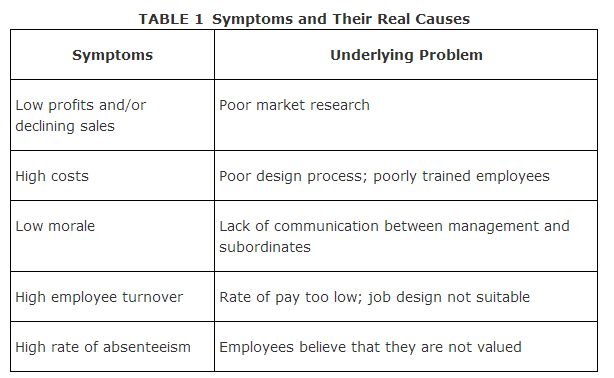

The most obviously troubling situations found in an organization can usually be identified as symptoms of underlying problems. (See Table for some examples of symptoms.) These symptoms all indicate that something is wrong with an organization, but they don't identify root causes. A successful manager doesn't just attack symptoms; he works to uncover the factors that cause these symptoms.

All managers want to make the best decisions. To do so, managers need to have the ideal resources — information, time, personnel, equipment, and supplies — and identify any limiting factors. Realistically, managers operate in an environment that normally doesn't provide ideal resources. For example, they may lack the proper budget or may not have the most accurate information or any extra time. So, they must choose to satisfice — to make the best decision possible with the information, resources, and time available.

Time pressures frequently cause a manager to move forward after considering only the first or most obvious answers. However, successful problem solving requires thorough examination of the challenge, and a quick answer may not result in a permanent solution. Thus, a manager should think through and investigate several alternative solutions to a single problem before making a quick decision.

One of the best known methods for developing alternatives is through brainstorming, where a group works together to generate ideas and alternative solutions. The assumption behind brainstorming is that the group dynamic stimulates thinking — one person's ideas, no matter how outrageous, can generate ideas from the others in the group. Ideally, this spawning of ideas is contagious, and before long, lots of suggestions and ideas flow. Brainstorming usually requires 30 minutes to an hour. The following specific rules should be followed during brainstorming sessions:

Concentrate on the problem at hand. This rule keeps the discussion very specific and avoids the group's tendency to address the events leading up to the current problem.

Entertain all ideas. In fact, the more ideas that come up, the better. In other words, there are no bad ideas. Encouragement of the group to freely offer all thoughts on the subject is important. Participants should be encouraged to present ideas no matter how ridiculous they seem, because such ideas may spark a creative thought on the part of someone else.

Refrain from allowing members to evaluate others' ideas on the spot. All judgments should be deferred until all thoughts are presented, and the group concurs on the best ideas.

Although brainstorming is the most common technique to develop alternative solutions, managers can use several other ways to help develop solutions. Here are some examples:

Nominal group technique. This method involves the use of a highly structured meeting, complete with an agenda, and restricts discussion or interpersonal communication during the decision‐making process. This technique is useful because it ensures that every group member has equal input in the decision‐making process. It also avoids some of the pitfalls, such as pressure to conform, group dominance, hostility, and conflict, that can plague a more interactive, spontaneous, unstructured forum such as brainstorming.

Delphi technique. With this technique, participants never meet, but a group leader uses written questionnaires to conduct the decision making.

No matter what technique is used, group decision making has clear advantages and disadvantages when compared with individual decision making. The following are among the advantages:

Groups provide a broader perspective.

Employees are more likely to be satisfied and to support the final decision.

Opportunities for discussion help to answer questions and reduce uncertainties for the decision makers.

These points are among the disadvantages:

This method can be more time‐consuming than one individual making the decision on his own.

The decision reached could be a compromise rather than the optimal solution.

Individuals become guilty of groupthink — the tendency of members of a group to conform to the prevailing opinions of the group.

Groups may have difficulty performing tasks because the group, rather than a single individual, makes the decision, resulting in confusion when it comes time to implement and evaluate the decision.

The results of dozens of individual‐versus‐group performance studies indicate that groups not only tend to make better decisions than a person acting alone, but also that groups tend to inspire star performers to even higher levels of productivity.

So, are two (or more) heads better than one? The answer depends on several factors, such as the nature of the task, the abilities of the group members, and the form of interaction. Because a manager often has a choice between making a decision independently or including others in the decision making, she needs to understand the advantages and disadvantages of group decision making.

The purpose of this step is to decide the relative merits of each idea. Managers must identify the advantages and disadvantages of each alternative solution before making a final decision.

Evaluating the alternatives can be done in numerous ways. Here are a few possibilities:

Determine the pros and cons of each alternative.

Perform a cost‐benefit analysis for each alternative.

Weight each factor important in the decision, ranking each alternative relative to its ability to meet each factor, and then multiply by a probability factor to provide a final value for each alternative.

Regardless of the method used, a manager needs to evaluate each alternative in terms of its

Feasibility — Can it be done?

Effectiveness — How well does it resolve the problem situation?

Consequences — What will be its costs (financial and nonfinancial) to the organization?

After a manager has analyzed all the alternatives, she must decide on the best one. The best alternative is the one that produces the most advantages and the fewest serious disadvantages. Sometimes, the selection process can be fairly straightforward, such as the alternative with the most pros and fewest cons. Other times, the optimal solution is a combination of several alternatives.

Sometimes, though, the best alternative may not be obvious. That's when a manager must decide which alternative is the most feasible and effective, coupled with which carries the lowest costs to the organization. (See the preceding section.) Probability estimates, where analysis of each alternative's chances of success takes place, often come into play at this point in the decision‐making process. In those cases, a manager simply selects the alternative with the highest probability of success.

Managers are paid to make decisions, but they are also paid to get results from these decisions. Positive results must follow decisions. Everyone involved with the decision must know his or her role in ensuring a successful outcome. To make certain that employees understand their roles, managers must thoughtfully devise programs, procedures, rules, or policies to help aid them in the problem‐solving process.

Ongoing actions need to be monitored. An evaluation system should provide feedback on how well the decision is being implemented, what the results are, and what adjustments are necessary to get the results that were intended when the solution was chosen.

In order for a manager to evaluate his decision, he needs to gather information to determine its effectiveness. Was the original problem resolved? If not, is he closer to the desired situation than he was at the beginning of the decision‐making process?

If a manager's plan hasn't resolved the problem, he needs to figure out what went wrong. A manager may accomplish this by asking the following questions:

Was the wrong alternative selected? If so, one of the other alternatives generated in the decision‐making process may be a wiser choice.

Was the correct alternative selected, but implemented improperly? If so, a manager should focus attention solely on the implementation step to ensure that the chosen alternative is implemented successfully.

Was the original problem identified incorrectly? If so, the decision‐making process needs to begin again, starting with a revised identification step.

Has the implemented alternative been given enough time to be successful? If not, a manager should give the process more time and re‐evaluate at a later date.