Physical growth is especially rapid during the first 2 years. An infant's birthweight generally doubles by 6 months and triples by the infant's first birthday. Similarly, a baby grows between 10 and 12 inches in length (or height), and the baby's proportions change during the first 2 years. The size of an infant's head decreases in proportion from 1/3 of the entire body at birth, to 1/4 at age 2, to 1/8 by adulthood.

Fetal and neonatal brain developments are also rapid. The lower, or subcortical, areas of the brain (responsible for basic life functions, like breathing) develop first, followed by the higher areas, or cortical areas (responsible for thinking and planning). Most brain changes occur prenatally and soon after birth. At birth, the neonate's brain weighs only 25 percent of that of an adult brain. By the end of the second year, the brain weighs about 80 percent; by puberty, it weighs nearly 100 percent of that of an adult brain.

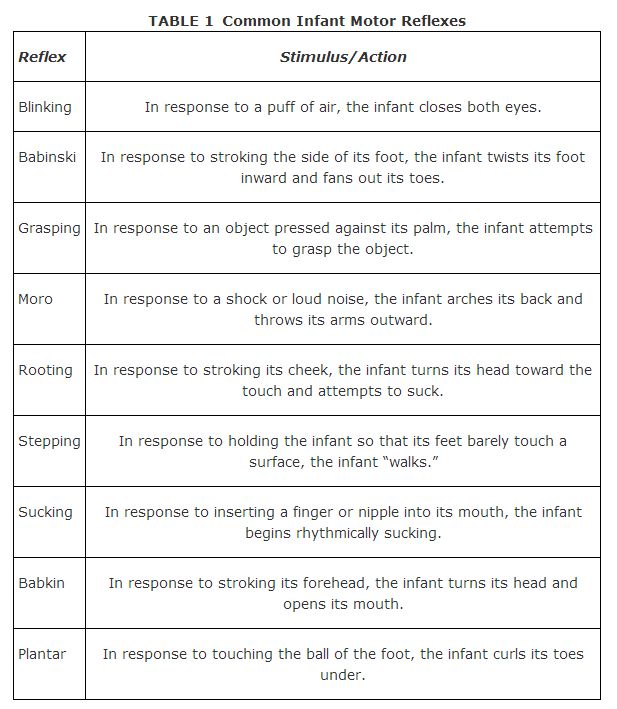

Because infants cannot endure on their own, newborns have specific built‐in or prewired abilities for survival and adaptive purposes. Reflexes are automatic reactions to stimulation that enable infants to respond to the environment before any learning has taken place. For instance, babies automatically suck when presented with a nipple, turn their heads when a parent speaks, grasp at a finger that is pressed into their hand, and startle when exposed to loud noises. Some reflexes, such as blinking, are permanent. Others, such as grasping, disappear after several months and eventually become voluntary responses. Common infant motor reflexes appear in Table 1.

Motor skills, or behavioral abilities, develop in conjunction with physical growth. In other words, infants must learn to engage in motor activities within the context of their changing bodies. At about 1 month, infants may lift their chins while lying flat on their stomachs. Within another month, infants may raise their chests from the same position. By the fourth month, infants may grasp rattles, as well as sit with support. By the fifth month, infants may roll over, and by the eighth month, infants may be able to sit without assistance. At about 10 months, toddlers may stand while holding onto an object for support. At about 14 months, toddlers may stand alone and perhaps even walk. Of course, these ages for each motor‐skill milestone are averages; the rates of physical and motor developments differ among children depending on a variety of factors, including heredity, the amount of activity the child participates in, and the amount of attention the child receives.

Motor development follows cephalocaudal (center and upper body) and proximodistal (extremities and lower body) patterns, so that motor skills become refined first from the center and upper body and later from the extremities and lower body. For example, swallowing is refined before walking, and arm movements are refined before hand movements.

Sensation and perception

Normal infants are capable of sensation, or the ability to respond to sensory information in the external world. These infants are born with functioning sensory organs, specialized structures of the body containing sensory receptors, which receive stimuli from the environment. Sensory receptors convert environmental energy into nervous system signals that the brain can understand and interpret. For example, the sensory receptors can convert light waves into visual images. The human senses include seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, and tasting.

Newborns are very nearsighted, but visual acuity, or ability, develops quickly. Although infant vision is not as good as adult vision, babies may respond visually to their surroundings from birth. Infants are particularly attracted to objects of light‐and‐dark contrasts, such as the human face. Depth perception also comes within a few months. Newborns may also respond to tastes, smells, and sounds, especially the sound of the human voice. In fact, newborns may almost immediately distinguish between the primary caregiver and others on the basis of sight, sound, and smell. Infant sensory abilities improve considerably during the first year.

Perception is the psychological process by which the human brain processes the sensory data collected by the sensory organs. Visually, infants are aware of depth (the relationship between foreground and background) and size and shape constancy (the consistent size and shape of objects). This latter ability is necessary for infants to learn about events and objects.

Learning

Learning is the process that results in relatively permanent change in behavior based on experience. Infants learn in a variety of ways. In classical conditioning (Pavlovian), learning occurs by association when a stimulus that evokes a certain response becomes associated with a different stimulus that originally did not cause that response. After the two stimuli associate in the subject's brain, the new stimulus then elicits the same response as the original. For instance, in psychologist John B. Watson's experiments with 11‐month‐old “Little Albert” in the 1920s, Watson classically conditioned Albert to fear a small white rat by pairing the sight of the rat with a loud, frightening noise. The once‐neutral white rat then became a feared stimulus through associative learning. Babies younger than age 3 months generally do not learn well through classical conditioning.

In operant conditioning (Skinnerian), learning occurs through the application of rewards and/or punishments. Reinforcements increase behaviors, while punishments decrease behaviors. Positive reinforcements are pleasant stimuli that are added to increase behavior; negative reinforcements are unpleasant stimuli that are removed to increase behavior. Because reinforcements always increase behavior, negative reinforcement is not the same as punishment. For example, a parent who spanks a child to make him stop misbehaving is using punishment, while a parent who takes away a child's privileges to make him study harder is using negative reinforcement. Shaping is the gradual application of operant conditioning. For example, an infant who learns that smiling elicits positive parental attention will smile at its parents more. Babies generally respond well to operant conditioning.

In observational learning, learning is achieved by observing and imitating others, as in the case of an infant who learns to clap by watching and imitating an older sibling. This form of learning is perhaps the fastest and most natural means by which infants and toddlers acquire new skills.

Health

Normal functioning of the newborn's various body systems is vital to its short‐term and long‐term health. Less than 1 percent of babies experience birth trauma, or injury incurred during birth. Longitudinal studies have shown that birth trauma, low birth weight, and early sickness can affect later physical and mental health but usually only if these children grow up in impoverished environments. Most babies tend to be rather hardy and are able to compensate for less‐than‐ideal situations early in life.

Nevertheless, some children are born with or are exposed to conditions that pose greater challenges. For example, phenylketonuria (PKU) is an inherited metabolic disorder in which a child lacks phenylalanine hydroxylase, the enzyme necessary to eliminate excess phynelalanine, an essential amino acid, from the body. Failure to feed a special diet to a child with PKU in the first 3 to 6 weeks of life will result in mentally retardation. Currently, all 50 states require PKU screening for newborns.

Poor nutrition, hygiene, and medical care also expose a child to unnecessary health risks. Parents need to ensure that their infant eats well, is clean, and receives adequate medical attention. For instance, proper immunization is critical in preventing such contagious diseases as diptheria, measles, mumps, Rubella, and polio. A licensed health‐care specialist can provide parents with charts detailing recommended childhood immunizations.

Infant mortality refers to the percentage of babies that die within the first year of life. In the United States today, about 9 babies out of every 1,000 live births die within the first year — a significantly smaller percentage than was reported only 50 years ago. This decrease in infant mortality is due to improvements in prenatal care and medicine in general. However, minority infants tend to be at a higher risk of dying, as are low birthweight, premature, and postmature babies. The leading causes of infant death are congenital birth defects, such as heart valve problems or pregnancy complications, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS).

SIDS is the unexpected and unexplained death of an apparently healthy infant. Postmortem autopsies of the SIDS infant usually provide no clues as to the cause of death. As far as authorities know, choking, vomiting, or suffocating does not cause SIDS. Two suspected causes include infant brain dysfunction and parental smoking, both prenatally and postnatally. In the United States, between 1 and 2 out of every 1,000 infants under age 1 die of SIDS each year.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|